In January, the Chinese company Deepseek released a reasoning AI model, called R1, that performs comparably to OpenAI's GPT-4o Turbo model on certain AI benchmarks but was developed with fewer resources at a much lower cost. Marc Andreessen called it “one of the most amazing and impressive breakthroughs I’ve ever seen,” even as NVIDIA’s stock plummeted by 17 percent — the largest ever one-day loss for a U.S. company.

While China’s AI competitiveness may have blindsided the tech world, the pharmaceutical industry has already had quite a few “DeepSeek Moments” of its own.

About one-fourth of all clinical trials and early drug development now happens in China. Large pharmaceutical companies in-license about a third of their experimental molecules from Chinese laboratories (meaning they purchase the rights to molecules developed by other research groups rather than discover them in-house), according to a report by Stifel. Just a couple of years ago, this number was about 10 percent.

"Ten years ago, a major [pharmaceutical company] seeking their next breakthrough molecule would have turned to an American or European biotech,” writes biotechnologist Alex Telford. “Today, they’re just as likely to license a molecule from a Chinese company. Chinese companies will often run the phase I trial in China for cheap, then flip it to a Western [pharmaceutical company] to run the expensive US trials and bring the drug to market."

The reason for this shift is due, in part, to policy. Chinese regulators have passed reforms that lower barriers to market entry and streamline approvals. Those reforms could hold lessons for U.S. regulators hoping to speed up drug development, too.

Impacts from China’s reforms can be seen by looking at clinical trial enrollment data. Such data is illuminating because enrollment numbers offer a measure of the administrative burden placed on new treatments as they move from concept to real-world testing. Patent filings and R&D budgets suggest how much a region invests in discovery, but clinical trial activity shows how projects navigate bureaucratic landscapes. By analyzing how enrollment rates respond to changes in policy, funding, and disease targets, we can see which approaches most effectively accelerate pharmaceutical innovation. Here’s what the data shows.

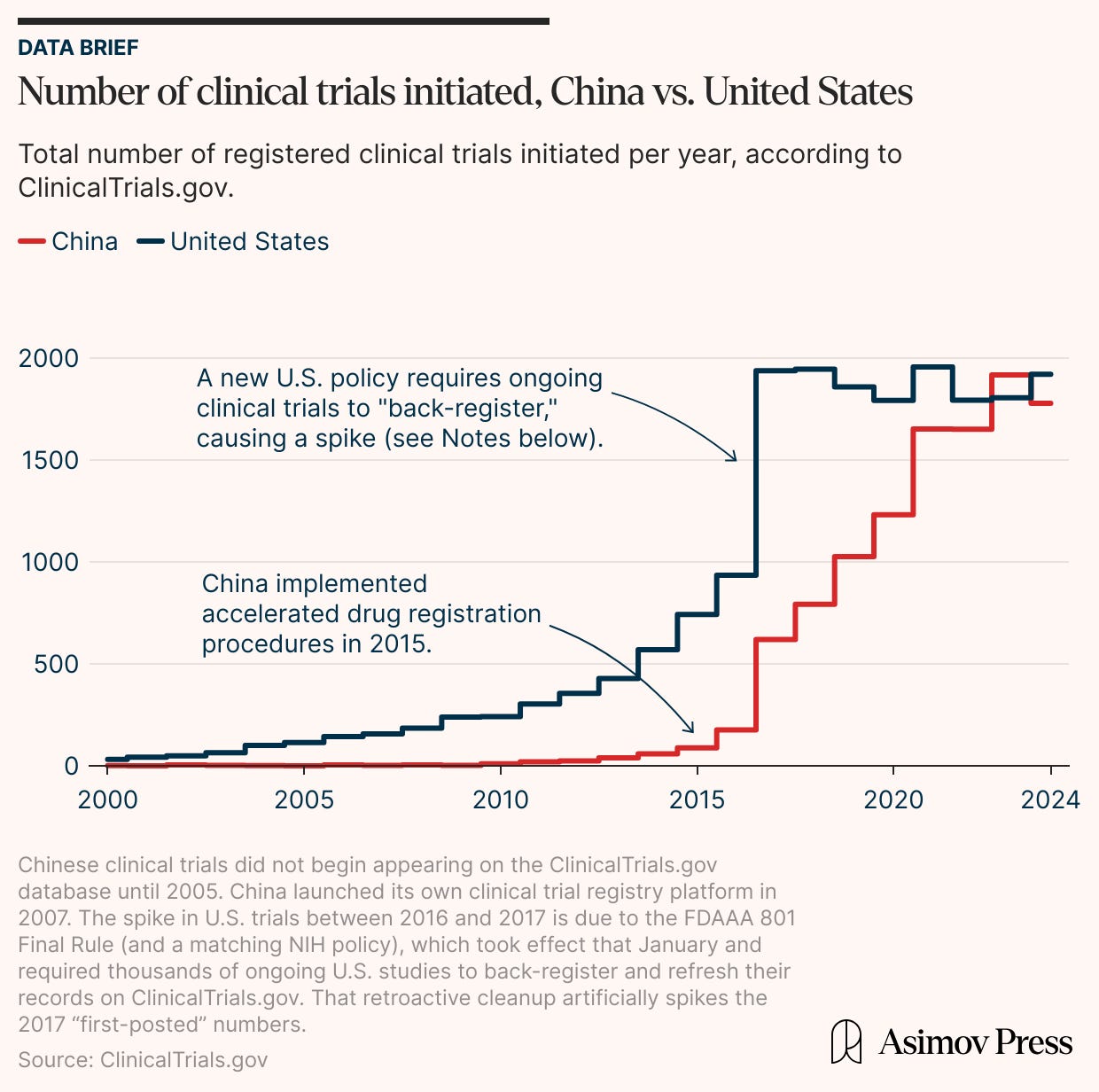

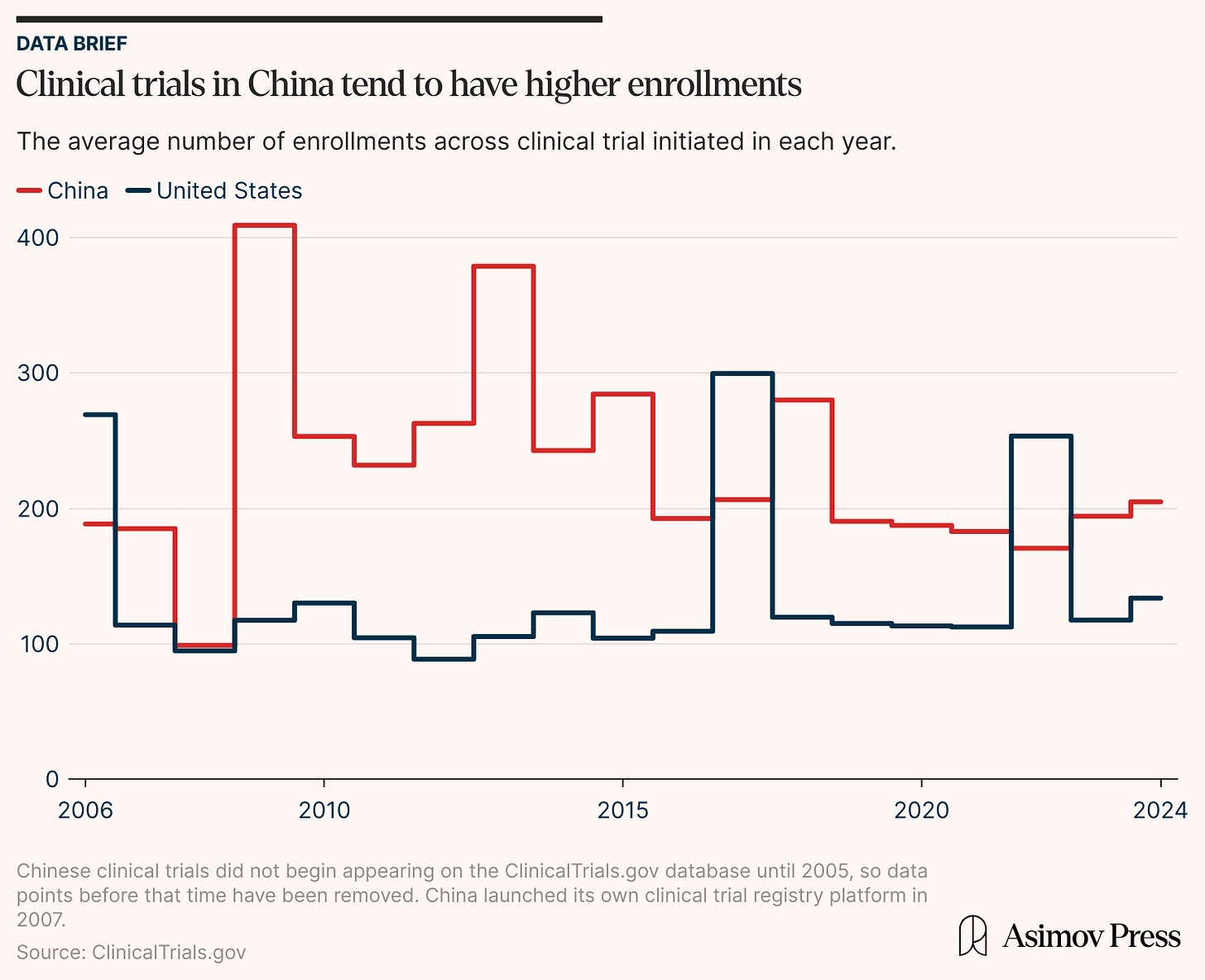

In the early 2010s, the number of clinical trials performed by American companies increased steadily but then leveled out at about 1,900 studies each year. China’s clinical trial numbers, on the other hand, remained relatively low until the mid-2010s. After the government streamlined approval policies, though, the number of clinical trials soared. Chinese companies matched the American clinical trial volume in the span of a few years while sustaining their average enrollment trajectory (at a marginally higher rate).

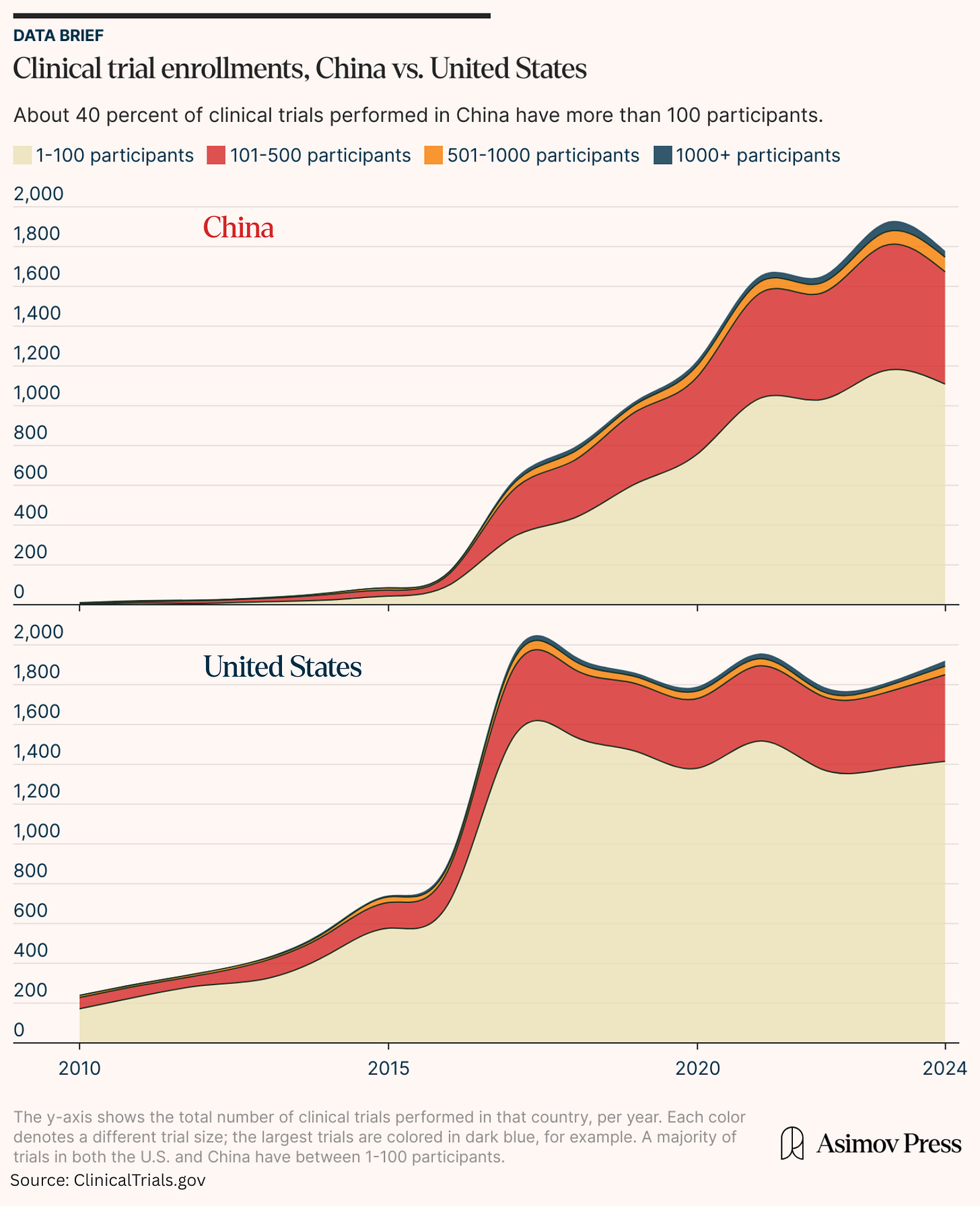

China’s jump in clinical trial enrollments doesn’t stem from a small number of large, late-phase trials (which would skew the mean), either. Rather, the number of original, new drugs originating in China has climbed from almost zero in 2010 to a figure, in 2023, that approaches American totals.

How did they do it?

Chinese regulators introduced several measures to speed up clinical trial approvals, including priority review and conditional approvals for new drugs. Drugs that qualify for priority review often address a critical, unmet clinical need, allowing them to go through an accelerated evaluation timeline.

In 2017, the NMPA (China’s drug regulator) also launched an “implied license” policy, which automatically authorizes a clinical trial if regulators voice no objections within 60 days. That same year, China joined the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) and updated its rules to accept overseas clinical trial data, reducing the need to repeat entire studies within China. This means that companies no longer need to repeat full trials in China if high-quality foreign results exist. Amgen’s XGEVA, a medication used to treat bone cancer, was approved in 2019 without further testing requirements based on a global Phase 2 study that included no clinical trial sites in China. Easier approvals and commercially viable results in multiple markets also led to international investment, which furthered the country’s biotech boom.

These reforms may help to explain why the number of Chinese clinical trials tripled between 2017 and 2023, from around 600 per year to nearly 2,000. Nor has the increased number of Chinese trials come at the expense of fewer enrollments.

A 2023 IQVIA report notes that industry-wide trial complexity declined after pandemic-era peaks, favoring numerous smaller studies. This trend is evident in the U.S. data, where over three-quarters of recent trials now enroll fewer than 100 participants. The result is that many American trials are smaller and underpowered, sometimes due to difficulties in recruiting participants. The LUNAR trial for lung cancer was forced to curtail its enrollment by half due to “slow accrual,” for example. More than 40 percent of clinical trials in China, by contrast, have high enrollment levels.

Ultimately, the clinical trial data tells a story of two paths: an American system that pioneered modern pharmaceutical development but now exhibits signs of plateau, and a rapidly ascending Chinese system that reformed its processes to maximize efficiency.

“Progress in biopharma is ultimately driven by a fast feedback loop of human data collection,” Telford writes. “China’s regulatory reforms have made it faster and cheaper to get drugs into humans, and the learning rate of the Chinese biopharma ecosystem seems a lot higher at the moment than the US or European ones.”

Recent proposals from The Clinical Trial Abundance Initiative reinforce this broader lesson, demonstrating that “democratizing” clinical research trials — through measures like expanding Medicaid coverage to draw more participants, eliminating unnecessary administrative burdens by simplifying paperwork, and allowing fair compensation — can increase both the speed and inclusivity of clinical trials. These plans face an uphill battle, though, especially given the ongoing funding constraints and polarized attitudes toward agencies like the NIH and FDA.

Still, these reforms reflect distinctly American roots, targeting domestic barriers such as fragmented insurance systems and institutional red tape. In contrast, China’s progress has leaned on centralized coordination, streamlined approval pathways, and top-down incentives for hospital participation. Though different in method, both models show how aligning regulatory structures with participation incentives can help unlock trial capacity and volume at scale.

Countries that adapt their frameworks to expedite start-up times, recognize credible foreign data, and balance the tradeoff between sufficient oversight and innovation-friendly policies stand to capture the next wave of drug discoveries. Japan, South Korea, and India are all following China’s example. The U.S. should be among them.

Thanks to Tony Kulesa for reading a draft of this.

Hiya Jain is graduating from Columbia University with training in history and neuroscience. She writes about the history of science on her Substack, Mundane Beauty.

Cite: Jain, H. “China’s Clinical Trial Boom.” Asimov Press (2025). DOI: 10.62211/56hr-91hg

Lead image by Ella Watkins-Dulaney.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the length of time required for new drug approvals in China (thanks to Egan Peltan for flagging the error.) An additional note explaining the large spike in U.S. trials between 2016 and 2017 has also been added.