In late 2022, I had a conversation with a senior engineer on the coming problem of “what to do when AI is writing most of the code”. His opinion, which I found striking at the time, was that engineers would transition from writing mostly “implementation” code, to mostly writing tests and specifications.

I remember thinking at the time that this was prescient. With three years of hindsight, it seems like things are trending in a different direction. I thought that the reason that testing and specifications would be useful was that AI agents would be struggling to “grok” coding for quite some time, and that you’d need to have robust specifications such that they could stumble toward correctness.

In reality, AI written tests were one of the first tasks I felt comfortable delegating. Unit tests are squarely in-distribution for what the models have seen on all public open source code. There’s a lot of unit tests in open source code, and they follow predictable patterns. I’d expect that the variance of implementation code – and the requirement for out-of-distribution patterns – is much higher than testing code. The result is that models are now quite good at translating English descriptions into quite crisp test cases.

System Design

There exists a higher level problem of holistic system behavior verification, though. Let’s take a quick diversion into systems design to see why.

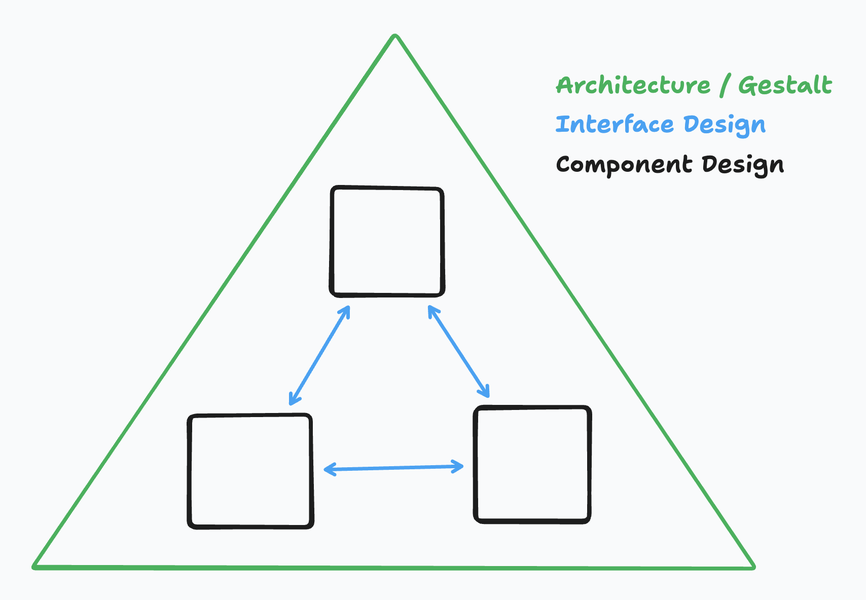

System design happens on multiple scales. You want systems to be robust – both in their runtime, and their ability to iteratively evolve. This nudges towards decomposing systems into distinct components, each of which can be internally complicated but exposes a firm interface boundary that allows you to abstract over this internal complexity.

If we design things well, we can swap out parts of our system without disrupting other parts or harming the top-level description of what the system does. We can also perform top-down changes iteratively – adding new components, and retiring old ones, at each level of description of the system.

This all requires careful thinking of how to build these interfaces and component boundaries in such a way that (1) there is a clean boundary between components and (2) that stringing all the components together actually produces the desired top-level behavior.

To do this effectively, we require maps of various levels of description of the system’s territory. My conjecture is that code is not a good map for this territory.

To be clear, I’ve found a lot of value in throwing out system diagram maps and looking directly at the code territory when debugging issues. However, code-level reasoning is often not the best level of abstraction to use for reasoning about systems. This is for a similar reason that “modeling all the individual molecules of a car” is not a great way to estimate that car’s braking distance.

LLMs have increasingly longer context windows, so one could naively say “just throw all the code in the context and have it work it out”. Perhaps. But this is still just clearly not the most efficient way to reason about large-scale systems.

Formal Verification

The promise of formal verification is that we can construct provably composable maps which still match the ground-level territory. Formal verification of code allows you to specify a system using mathematical proofs, and then exhaustively prove that a system is correct. As an analogy: unit tests are like running an experiment. Each passing test is an assertion that, for the conditions checked, the code is correct. There could still exist some untested input that would demonstrate incorrect behavior. You only need one negative test to show the code is incorrect, but only a provably exhaustive set of inputs would be sufficient to show the code is fully correct. Writing a formal verification of a program is more like writing a proof. Writing a self-consistent proof is sufficient to show that the properties you’ve proven always hold.

I saw Martin Kleppmann’s “Prediction: AI will make formal verification go mainstream” right after I posted “The Decline of the Software Drafter?”, which became the inspiration for this post. Kleppmann’s argument is that, just as the cost of generating code is coming down, so too will the cost of formal verification of code:

For example, as of 2009, the formally verified seL4 microkernel consisted of 8,700 lines of C code, but proving it correct required 20 person-years and 200,000 lines of Isabelle code – or 23 lines of proof and half a person-day for every single line of implementation. Moreover, there are maybe a few hundred people in the world (wild guess) who know how to write such proofs, since it requires a lot of arcane knowledge about the proof system.

…

If formal verification becomes vastly cheaper, then we can afford to verify much more software. But on top of that, AI also creates a need to formally verify more software: rather than having humans review AI-generated code, I’d much rather have the AI prove to me that the code it has generated is correct. If it can do that, I’ll take AI-generated code over handcrafted code (with all its artisanal bugs) any day!

I’ve long been interested in formal verification tools like TLA+ and Rocq (née Coq). I haven’t (yet) been able to justify to myself spending all that much time on them. I think that’s changing: the cost of writing code is coming down dramatically. The cost of reviewing and maintaining it is also coming down, but at a slower rate. I agree with Kleppmann that we need systematic tooling for dealing with this mismatch.

Wishcasting a future world, I would be excited to see something like:

- One starts with a high-level system specification, in English.

- This specification is spun out into multiple TLA+ models at various levels of component specificity.

- These models would allow us to determine the components that are load-bearing for system correctness.

- The most critical set of load-bearing components are implemented with a corresponding formal verification proof, in something like Rocq.

- The rest of the system components are still audited by an LLM to ensure they correctly match the behavior of their associated component in the TLA+ spec.

The biggest concern to me related to formal verification is the following two excerpts, first from Kleppmann, and then from Hillel Wayne, a notable proponent of TLA+:

There are maybe a few hundred people in the world (wild guess) who know how to write such proofs, since it requires a lot of arcane knowledge about the proof system. – Martin Kleppmann

TLA+ is one of the more popular formal specification languages and you can probably fit every TLA+ expert in the world in a large schoolbus. – Hillel Wayne

For formal verification to be useful in practice, at least some of the arcane knowledge of its internals will need to be broadly disseminated. Reviewing an AI-generated formal spec of a problem won’t be useful if you don’t have enough knowledge of the proof system to poke holes in what the AI came up with.

I’d argue that undergraduate Computer Science programs should allocate some of their curriculum to formal verification. After all, students should have more time on their hands as they delegate implementation of their homework to AI agents.