Stephen Hawking begins A Brief History of Time with this story:

A well-known scientist (some say it was Bertrand Russell) once gave a public lecture on astronomy. He described how the earth orbits around the sun and how the sun, in turn, orbits around the center of a vast collection of stars called our galaxy. At the end of the lecture, a little old lady at the back of the room got up and said: “What you have told us is rubbish. The world is really a flat plate supported on the back of a giant tortoise.” The scientist gave a superior smile before replying, “What is the tortoise standing on?” “You're very clever, young man, very clever,” said the old lady. “But it's turtles all the way down!”

Scientists today are pretty sure that the universe is not actually turtles all the way down, but we can create that kind of situation in other contexts. For example, here we have video monitors all the way down and set theory books all the way down, and shopping carts all the way down.

And here's a computer storage equivalent:

look inside r.zip.

It's zip files all the way down:

each one contains another zip file under the name r/r.zip.

(For the die-hard Unix fans, r.tar.gz is

gzipped tar files all the way down.)

Like the line of shopping carts, it never ends,

because it loops back onto itself: the zip file contains itself!

And it's probably less work to put together a self-reproducing zip file

than to put together all those shopping carts,

at least if you're the kind of person who would read this blog.

This post explains how.

Before we get to self-reproducing zip files, though, we need to take a brief detour into self-reproducing programs.

Self-reproducing programs

The idea of self-reproducing programs dates back to the 1960s. My favorite statement of the problem is the one Ken Thompson gave in his 1983 Turing Award address:

In college, before video games, we would amuse ourselves by posing programming exercises. One of the favorites was to write the shortest self-reproducing program. Since this is an exercise divorced from reality, the usual vehicle was FORTRAN. Actually, FORTRAN was the language of choice for the same reason that three-legged races are popular.

More precisely stated, the problem is to write a source program that, when compiled and executed, will produce as output an exact copy of its source. If you have never done this, I urge you to try it on your own. The discovery of how to do it is a revelation that far surpasses any benefit obtained by being told how to do it. The part about “shortest” was just an incentive to demonstrate skill and determine a winner.

Spoiler alert! I agree: if you have never done this, I urge you to try it on your own. The internet makes it so easy to look things up that it's refreshing to discover something yourself once in a while. Go ahead and spend a few days figuring out. This blog will still be here when you get back. (If you don't mind the spoilers, the entire Turing award address is worth reading.)

(Spoiler blocker.)

http://www.robertwechsler.com/projects.html

Let's try to write a Python program that prints itself.

It will probably be a print statement, so here's a first attempt,

run at the interpreter prompt:

>>> print 'hello'

hello

That didn't quite work. But now we know what the program is, so let's print it:

>>> print "print 'hello'"

print 'hello'

That didn't quite work either. The problem is that when you execute a simple print statement, it only prints part of itself: the argument to the print. We need a way to print the rest of the program too.

The trick is to use recursion: you write a string that is the whole program, but with itself missing, and then you plug it into itself before passing it to print.

>>> s = 'print %s'; print s % repr(s)

print 'print %s'

Not quite, but closer: the problem is that the string s isn't actually

the program. But now we know the general form of the program:

s = '%s'; print s % repr(s).

That's the string to use.

>>> s = 's = %s; print s %% repr(s)'; print s % repr(s)

s = 's = %s; print s %% repr(s)'; print s % repr(s)

Recursion for the win.

This form of self-reproducing program is often called a quine, in honor of the philosopher and logician W. V. O. Quine, who discovered the paradoxical sentence:

“Yields falsehood when preceded by its quotation”

yields falsehood when preceded by its quotation.

The simplest English form of a self-reproducing quine is a command like:

Print this, followed by its quotation:

“Print this, followed by its quotation:”

There's nothing particularly special about Python that makes quining possible. The most elegant quine I know is a Scheme program that is a direct, if somewhat inscrutable, translation of that sentiment:

((lambda (x) `(,x ',x)) '(lambda (x) `(,x ',x)))

I think the Go version is a clearer translation, at least as far as the quoting is concerned:

/* Go quine */ package main import "fmt" func main() { fmt.Printf("%s%c%s%c\n", q, 0x60, q, 0x60) } var q = `/* Go quine */ package main import "fmt" func main() { fmt.Printf("%s%c%s%c\n", q, 0x60, q, 0x60) } var q = `

(I've colored the data literals green throughout to make it clear what is program and what is data.)

The Go program has the interesting property that, ignoring the pesky newline

at the end, the entire program is the same thing twice (/* Go quine */ ... q = `).

That got me thinking: maybe it's possible to write a self-reproducing program

using only a repetition operator.

And you know what programming language has essentially only a repetition operator?

The language used to encode Lempel-Ziv compressed files

like the ones used by gzip and zip.

Self-reproducing Lempel-Ziv programs

Lempel-Ziv compressed data is a stream of instructions with two basic

opcodes: literal(n) followed by

n bytes of data means write those n bytes into the

decompressed output,

and repeat(d, n)

means look backward d bytes from the current location

in the decompressed output and copy the n bytes you find there

into the output stream.

The programming exercise, then, is this: write a Lempel-Ziv program

using just those two opcodes that prints itself when run.

In other words, write a compressed data stream that decompresses to itself.

Feel free to assume any reasonable encoding for the literal

and repeat opcodes.

For the grand prize, find a program that decompresses to

itself surrounded by an arbitrary prefix and suffix,

so that the sequence could be embedded in an actual gzip

or zip file, which has a fixed-format header and trailer.

Spoiler alert! I urge you to try this on your own before continuing to read. It's a great way to spend a lazy afternoon, and you have one critical advantage that I didn't: you know there is a solution.

(Spoiler blocker.)

.jpg)

http://www.robertwechsler.com/thebest.html

By the way, here's r.gz, gzip files all the way down.

$ gunzip < r.gz > r $ cmp r r.gz $

The nice thing about r.gz is that even broken web browsers

that ordinarily decompress downloaded gzip data before storing it to disk

will handle this file correctly!

Enough stalling to hide the spoilers.

Let's use this shorthand to describe Lempel-Ziv instructions:

Ln and Rn are

shorthand for literal(n) and

repeat(n, n),

and the program assumes that each code is one byte.

L0 is therefore the Lempel-Ziv no-op;

L5 hello prints hello;

and so does L3 hel R1 L1 o.

Here's a Lempel-Ziv program that prints itself. (Each line is one instruction.)

| Code | Output | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| no-op | L0 | |||

| no-op | L0 | |||

| no-op | L0 | |||

| print 4 bytes | L4 L0 L0 L0 L4 | L0 L0 L0 L4 | ||

| repeat last 4 printed bytes | R4 | L0 L0 L0 L4 | ||

| print 4 bytes | L4 R4 L4 R4 L4 | R4 L4 R4 L4 | ||

| repeat last 4 printed bytes | R4 | R4 L4 R4 L4 | ||

| print 4 bytes | L4 L0 L0 L0 L0 | L0 L0 L0 L0 |

(The two columns Code and Output contain the same byte sequence.)

The interesting core of this program is the 6-byte sequence

L4 R4 L4 R4 L4 R4, which prints the 8-byte sequence R4 L4 R4 L4 R4 L4 R4 L4.

That is, it prints itself with an extra byte before and after.

When we were trying to write the self-reproducing Python program,

the basic problem was that the print statement was always longer

than what it printed. We solved that problem with recursion,

computing the string to print by plugging it into itself.

Here we took a different approach.

The Lempel-Ziv program is

particularly repetitive, so that a repeated substring ends up

containing the entire fragment. The recursion is in the

representation of the program rather than its execution.

Either way, that fragment is the crucial point.

Before the final R4, the output lags behind the input.

Once it executes, the output is one code ahead.

The L0 no-ops are plugged into

a more general variant of the program, which can reproduce itself

with the addition of an arbitrary three-byte prefix and suffix:

| Code | Output | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| print 4 bytes | L4 aa bb cc L4 | aa bb cc L4 | ||

| repeat last 4 printed bytes | R4 | aa bb cc L4 | ||

| print 4 bytes | L4 R4 L4 R4 L4 | R4 L4 R4 L4 | ||

| repeat last 4 printed bytes | R4 | R4 L4 R4 L4 | ||

| print 4 bytes | L4 R4 xx yy zz | R4 xx yy zz | ||

| repeat last 4 printed bytes | R4 | R4 xx yy zz |

(The byte sequence in the Output column is aa bb cc, then

the byte sequence from the Code column, then xx yy zz.)

It took me the better part of a quiet Sunday to get this far,

but by the time I got here I knew the game was over

and that I'd won.

From all that experimenting, I knew it was easy to create

a program fragment that printed itself minus a few instructions

or even one that printed an arbitrary prefix

and then itself, minus a few instructions.

The extra aa bb cc in the output

provides a place to attach such a program fragment.

Similarly, it's easy to create a fragment to attach

to the xx yy zz that prints itself,

minus the first three instructions, plus an arbitrary suffix.

We can use that generality to attach an appropriate

header and trailer.

Here is the final program, which prints itself surrounded by an

arbitrary prefix and suffix.

[P] denotes the p-byte compressed form of the prefix P;

similarly, [S] denotes the s-byte compressed form of the suffix S.

| Code | Output | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| print prefix | [P] |

P |

||

| print p+1 bytes | Lp+1 [P] Lp+1 |

[P] Lp+1 |

||

| repeat last p+1 printed bytes | Rp+1 |

[P] Lp+1 |

||

| print 1 byte | L1 Rp+1 |

Rp+1 |

||

| print 1 byte | L1 L1 |

L1 |

||

| print 4 bytes | L4 Rp+1 L1 L1 L4 |

Rp+1 L1 L1 L4 |

||

| repeat last 4 printed bytes | R4 |

Rp+1 L1 L1 L4 |

||

| print 4 bytes | L4 R4 L4 R4 L4 |

R4 L4 R4 L4 |

||

| repeat last 4 printed bytes | R4 |

R4 L4 R4 L4 |

||

| print 4 bytes | L4 R4 L0 L0 Ls+1 |

R4 L0 L0 Ls+1 |

||

| repeat last 4 printed bytes | R4 |

R4 L0 L0 Ls+1 |

||

| no-op | L0 |

|||

| no-op | L0 |

|||

| print s+1 bytes | Ls+1 Rs+1 [S] |

Rs+1 [S] |

||

| repeat last s+1 bytes | Rs+1 |

Rs+1 [S] |

||

| print suffix | [S] |

S |

(The byte sequence in the Output column is P, then

the byte sequence from the Code column, then S.)

Self-reproducing zip files

Now the rubber meets the road. We've solved the main theoretical obstacle to making a self-reproducing zip file, but there are a couple practical obstacles still in our way.

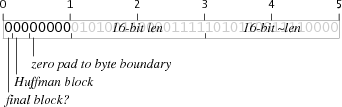

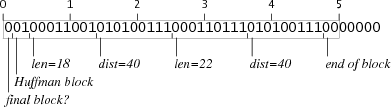

The first obstacle is to translate our self-reproducing Lempel-Ziv program, written in simplified opcodes, into the real opcode encoding. RFC 1951 describes the DEFLATE format used in both gzip and zip: a sequence of blocks, each of which is a sequence of opcodes encoded using Huffman codes. Huffman codes assign different length bit strings to different opcodes, breaking our assumption above that opcodes have fixed length. But wait! We can, with some care, find a set of fixed-size encodings that says what we need to be able to express.

In DEFLATE, there are literal blocks and opcode blocks. The header at the beginning of a literal block is 5 bytes:

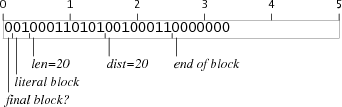

If the translation of our L opcodes above

are 5 bytes each, the translation of the R opcodes

must also be 5 bytes each, with all the byte counts

above scaled by a factor of 5.

(For example, L4 now has a 20-byte argument,

and R4 repeats the last 20 bytes of output.)

The opcode block

with a single repeat(20,20) instruction falls well short of

5 bytes:

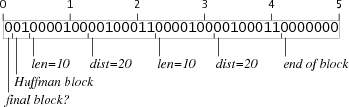

Luckily, an opcode block containing two

repeat(20,10) instructions has the same effect and is exactly 5 bytes:

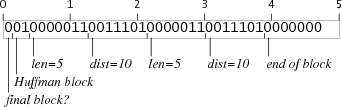

Encoding the other sized repeats

(Rp+1 and

Rs+1)

takes more effort

and some sleazy tricks, but it turns out that

we can design 5-byte codes that repeat any amount

from 9 to 64 bytes.

For example, here are the repeat blocks for 10 bytes and for 40 bytes:

The repeat block for 10 bytes is two bits too short, but every repeat block is followed by a literal block, which starts with three zero bits and then padding to the next byte boundary. If a repeat block ends two bits short of a byte but is followed by a literal block, the literal block's padding will insert the extra two bits. Similarly, the repeat block for 40 bytes is five bits too long, but they're all zero bits. Starting a literal block five bits too late steals the bits from the padding. Both of these tricks only work because the last 7 bits of any repeat block are zero and the bits in the first byte of any literal block are also zero, so the boundary isn't directly visible. If the literal block started with a one bit, this sleazy trick wouldn't work.

The second obstacle is that zip archives (and gzip files) record a CRC32 checksum of the uncompressed data. Since the uncompressed data is the zip archive, the data being checksummed includes the checksum itself. So we need to find a value x such that writing x into the checksum field causes the file to checksum to x. Recursion strikes back.

The CRC32 checksum computation interprets the entire file as a big number and computes the remainder when you divide that number by a specific constant using a specific kind of division. We could go through the effort of setting up the appropriate equations and solving for x. But frankly, we've already solved one nasty recursive puzzle today, and enough is enough. There are only four billion possibilities for x: we can write a program to try each in turn, until it finds one that works.

If you want to recreate these files yourself, there are a

few more minor obstacles, like making sure the tar file is a multiple

of 512 bytes and compressing the rather large zip trailer to

at most 59 bytes so that Rs+1 is

at most R64.

But they're just a simple matter of programming.

So there you have it:

r.gz (gzip files all the way down),

r.tar.gz (gzipped tar files all the way down),

and

r.zip (zip files all the way down).

I regret that I have been unable to find any programs

that insist on decompressing these files recursively, ad infinitum.

It would have been fun to watch them squirm, but

it looks like much less sophisticated

zip bombs have spoiled the fun.

If you're feeling particularly ambitious, here is rgzip.go, the Go program that generated these files. I wonder if you can create a zip file that contains a gzipped tar file that contains the original zip file. Ken Thompson suggested trying to make a zip file that contains a slightly larger copy of itself, recursively, so that as you dive down the chain of zip files each one gets a little bigger. (If you do manage either of these, please leave a comment.)

P.S. I can't end the post without sharing my favorite self-reproducing program: the one-line shell script #!/bin/cat.