TLDR: Yes, you can fit about 7 seconds of audio into 16K of flash and still have room for code. And you can even play LPC encoded audio on a 10 cent MCU.

There’s quite a lot more detail in this video (and of course you can hear the audio!).

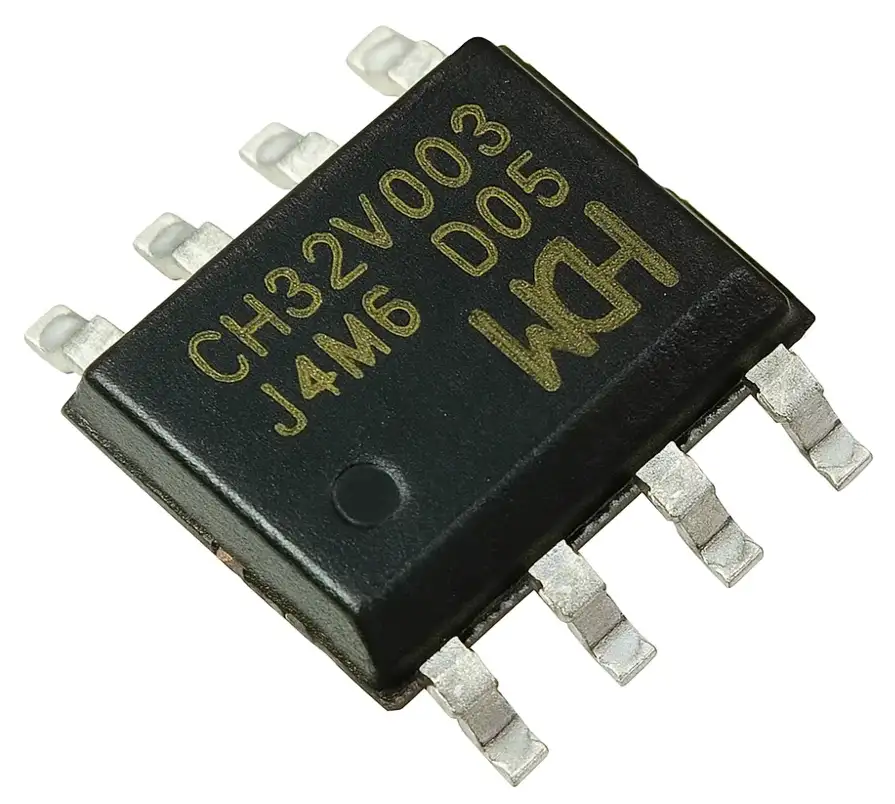

In the previous project, I had this ultra-cheap CH32V003 microcontroller playing simple tunes on a tiny SMD buzzer. It was just toggling a GPIO pin at musical note frequencies – 1-bit audio output – and it sounded surprisingly decent. That was a fun start, but now it’s time to push this little $0.10 MCU even further: can we make it actually talk?

Spoiler: Yes, we can! (well, there wouldn’t be much of a blog post if we couldn’t) This 8-pin RISC-V chip is now producing sampled audio data and spoken words. We’re really stretching the limits of what you can fit in 16 KB of flash.

From Beeps to Actual Audio

Moving from simple beeps to real audio meant using the microcontroller’s PWM output as a rudimentary DAC. Instead of just on/off beeping, I’m driving a waveform at an 8 kHz sample rate using a high-frequency PWM on the output pin. The hardware is the same tiny board as before – but I’ve swapped the small SMD buzzer for a small speaker. The buzer works too, but it’s quieter and very tinny.

The sample I wanted to test with is just over 6 seconds in length - it’s the iconic “Open the pod bay doors HAL…” sequence from 2001.

If we keep this audio at 16-bit PCM, 8kHZ, we’d need about 96KB – way beyond our 16 KB flash! And remember, that 16 KB has to hold both the audio data and our playback code. Clearly some aggressive compression is required.

| Format | Sample Rate | Bits/Sample | Size | Fits in 16KB? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD Quality | 44.1 kHz | 16-bit | 529 KB | ❌ 33× too big! |

| Phone Quality | 16 kHz | 16-bit | 192 KB | ❌ 12× too big! |

| Basic PCM | 8 kHz | 8-bit | 48 KB | ❌ 3× too big! |

| 4-bit ADPCM (IMA) | 8 kHz | 4-bit | 24 KB | ❌ 1.5× too big |

| QOA (Quite OK Audio) | 8 kHz | 3.2-bit | 19 KB | ❌ Still too big! |

| 2-bit ADPCM | 8 kHz | 2-bit | 12 KB | ✅ Fits! |

I considered a few encoding options for compressing the audio.

- 8-bit PCM: Simply using 8-bit samples at 8 kHz cuts size in half (to ~47 KB for 6s), but that’s still about 3× too large for our flash.

- 4-bit ADPCM: Adaptive Differential PCM is a simple lossy compression that could quarter the size. In theory 6 seconds would be ~24 KB – much closer to fitting,

- “Quite OK Audio” (QOA): This is nice codec that packs audio into about 3.2 bits per sample (roughly 1/5 the size of 16-bit PCM)

- 2-bit ADPCM: Going even further with ADPCM, using only 2 bits per sample gives a 4:1 compression relative to 8-bit audio – that’s 75% storage savings.

2-bit ADPCM is definitely the winner here. Our 6-second clip shrinks to under 12 KB, which comfortably fits in flash with room for code. This looked like the winner, provided the audio quality was acceptable. The decoder for 2-bit ADPCM is also very lightweight (my implementation compiled to under just over 1K of code - 1340 bytes!). It’s definitely low quality - but it actually sounds surprisingly ok.

How does 2-bit ADPCM work?

It’s actually a very simple algorithm. Both the encoder and decoder maintain a predicted signal value and a step size index into a predefined table. Each 2-bit code tells the decoder how to adjust the current prediction and the step size index. In essence, we’re coding the difference between the real audio and our prediction, with only four possible levels (since 2 bits gives 4 values). After each sample, the algorithm adapts: if the prediction error was large, we move to a bigger step size (to allow larger changes); if the error was small, we use a smaller step size for finer resolution. This adaptive step is what makes it ADPCM (Adaptive Differential PCM).

Our codes are as follows:

00(0): Go down by 1 step - subtract the step size from our current prediction01(1): Go up by 1 step - add the step size to our current prediction10(2): Go down by 2 steps - subtract the 2 x step size from our current prediction11(3): Go up by 2 steps - add the 2 x step size to our current prediction

Even with this very high level of compression, the predicted waveform manages to track the original audio surprisingly well. The above graph shows a small snippet of the audio: the blue line is the original waveform and the yellow line is the ADPCM decoder’s output.

They’re not identical (and we wouldn’t expect them to be), but the general shape is preserved. When you play it back through the little speaker, it’s recognizable and surprisingly good.

To make my life easier, I built a quick conversion tool to encode WAV files into this 2-bit ADPCM format. The tool lets me drag-and-drop a WAV, and it gives you the files with the data that can ve dropped into the firmware code.

LPC Speech Synthesis

Six seconds of audio is cool, but what about longer phrases or even arbitrary speech? Storing anything much longer with raw or ADPCM audio would quickly fill the 16K of flash.

For my second experiment, I tried something different: instead of recorded waveform audio, I used an old-school speech synthesis approach. This leverages the fact that spoken language can be encoded very compactly by modeling the human voice, rather than storing the raw sound. Specifically, I integrated a library called Talkie.

Talkie is a software implementation of the Texas Instruments LPC speech synthesis architecture from the late 1970s. This was implemented in a variety of chips, most commonly the TMS5220 and TMS5100 speech chips.

These were used in things like the original Speak & Spell, arcade games like early Star Wars, and speech add-ons for home computers (e.g. the BBC Micro).

The Talkie library (originally by Peter Knight, later added to by Adafruit) comes with a big set of examples and vocabulary. It’s also possible to extract examples from old ROMs from arcade games.

Each phrase or word only takes a few hundred bytes or even less, so you can fit quite a lot of speech into a few kilobytes of flash. The trade-off is that the voice has a very computer-esque timbre – think of the Speak & Spell’s voice. It’s clearly synthetic, but still understandable.

To say custom sentences not in the library, you either concatenate the available words/phonemes (which can be clunky), or you need to generate new LPC data. The original tools for this are a bit obscure – there’s BlueWizard (a classic Mac app) and PythonWizard (a command-line tool with TK GUI) which can analyze WAV files and produce LPC data.

I gave both a try with some success (and a few headaches setting them up). In the end, I cheated a bit and used an AI coding assistant to help me create a streamlined online tool for this.

The result is a little web app where I can upload a recording of, say, my own voice, and it outputs the LPC data. It even lets me play back the synthesized voice in-browser to check it.

So there we have it – our 10¢ microcontroller now has a voice! By using 2-bit ADPCM compression, we can store short audio clips (up to around 8 seconds) even in 16 KB of flash, and play them back via PWM with decent fidelity.

And with the Talkie LPC speech synthesis, we can make the device “speak” lots of words and phrases with only a tiny memory footprint.

If you want to hear it for yourself, check out the video demo linked at the top of this post. In the video, you’ll see (and hear) the WarGames clip and the Star Wars quotes running on the hardware. It’s honestly amazing what these cheap little MCUs can do. We’re really pushing the boundaries of cheap hardware here.

You can find all my code on GitHub in this repository.