One of the most controversial things I believe about good software design is that your code should be more flexible than your domain model. This is in direct opposition to a lot of popular design advice, which is all about binding your code to your domain model as tightly as possible.

For instance, a popular principle for good software design is to make invalid states unrepresentable. This usually means doing two things:

- Enforcing a single source of truth in your database schema. If users and profiles are associated with a

user_idon theprofilestable, don’t also put aprofile_idon theuserstable, because then you could have a mismatch. - Enforcing stricter types. If you use an “published/pending” enum to track comment status instead of a string field, you don’t have to worry about weird strings you don’t expect.

I can see why people like this principle. The more you can constrain your software to match your domain model, the easier it will be easier to reason about. However, it’s possible to take it too far. In my view, your software should include as few hard constraints as possible. Real-world software is already subject to the genuinely hard constraints of the real world. If you add further constraints to make your software neater, you risk making it difficult to change when you really, really have to. Because of this, good software design should allow the system to represent some invalid states.

State machines should allow arbitrary state transitions

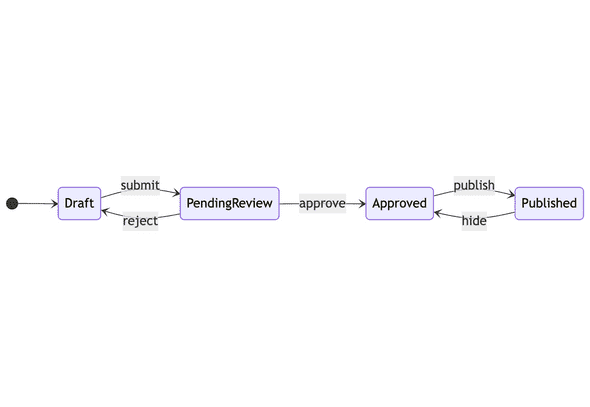

For instance, it’s popular advice to represent many complex software processes as a “state machine”. Instead of writing ad-hoc code, you can label the various states the system can be in and define a graph of which states can transition to which other states. The edges of that graph become your system’s actions.

Here’s an example. If you run an app marketplace, you might thus define a set of states like “draft”, “pending review”, “approved”, and “published”. The actions that connect those states might be “submit”, “approve”, “reject”, “publish” and “hide”.

Note that you can only submit a draft app, you can only reject a pending app, you can only hide a published app, and so on. These constraints are the entire point of using a state machine. It’s the constraints that make the system much easier to reason about: instead of a ton of app state that could all be modified independently, you have four possible states and five possible actions.

The problem, of course, is in the edge cases. What happens when you need to account for “official” apps, which are developed internally and shouldn’t go through the normal review process? What happens when a key partner’s app is mistakenly rejected, and the engineering team is asked to “un-reject” it without forcing the partner to resubmit? What happens when a published app has to be hidden in a way that prevents it from being published again?

There are two ways to handle edge cases in a state machine. The first is to update the design. Maybe you can add an “official” status that can directly move to “published” without review, or a “manually-approved” action that can take an app straight from “draft” to “approved”, or a “hide-and-reject” action that can take an app from “published” back to “draft”. However, this can dramatically complicate the design:

The second way to handle edge cases is to allow arbitrary state transitions. In other words, to relax the constraint that forces state machines to transition only via predefined actions. This keeps the core design simple, at the cost of allowing exceptions.

In almost all cases, you should update the design (for instance, any app marketplace needs a “hide-and-reject” action handy). But you need to remain flexible enough to allow some arbitrary transitions. Any engineering team that owns a customer-facing service will always be asked to do arbitrary one-off tasks. If you redesign your software each time to allow them, you will end up in a nasty tangle. Thus you should ensure that your technical constraints are not absolute.

Foreign key constraints

Abnother classic example of this is foreign key constraints. In a relational database, tables are related by primary key (typically ID): a posts table will have a user_id column to show which user owns which post, corresponding to the value of the id column in the users table. When you want to fetch the posts belonging to user 3, you’ll run SQL like SELECT * FROM posts WHERE user_id = 3.

A foreign key constraint forces user_id to correspond to an actual row in the users table. If you try to create or update a post with user_id 999, and there is no user with that id, the foreign key constraint will cause the SQL query to fail.

This sounds great, right? A record pointing at a non-existent user is in an invalid state. Shouldn’t we want it to be impossible to represent invalid states? However, many large tech companies - including the two I’ve worked for, GitHub and Zendesk - deliberately choose not to use foreign key constraints. Why not?

The main reason is flexibility. In practice, it’s much easier to deal with some illegal states in application logic (like posts with no user attached) than it is to deal with the constraint. With foreign key constraints, you have to delete all related records when a parent record is deleted. That might be okay for users and posts - though it could become a very expensive operation - but what about relationships that are less solid? If a post has a reviewer_id, what happens when that reviewer’s account is deleted? It doesn’t seem right to delete the post, surely. And so on.

If you want to change the database schema, foreign key constraints can be a big problem. Maybe you want to move a table to a different database cluster or shard. If it has any foreign key relationships to other tables, watch out! If you’re not also moving those tables over, you’ll have to remove the foreign key constraint then anyway. Even if you are moving those tables too, it’s a giant hassle to move the data in a way that’s compliant with the constraint, because you can’t just replicate a single table at a time - you have to move the data in chunks that keep the foreign key relationships intact.

The principle here is the same as with state machines: at some point you will be forced to do something that violates your tidy constraints, and if you’ve made those constraints truly immovable you’re buying yourself a lot of trouble.

Protocol buffers and required fields

For a third example, consider Protocol Buffers. Protobufs are Google’s popular open-source serialization format. The first iteration of protobufs allowed you to tag fields as required. If a client parsing a protobuf saw it was missing a required field, that client would reject the message. This sounds sensible enough, right? Many kinds of message don’t make any sense without certain values, so why not encode that constraint into the serialization layer? Isn’t it good to make invalid messages impossible to represent?

However, in the second iteration, Google dropped the ability to mark any field as required. This was a controversial decision. In fact, many believe that all proto fields should always be required, on the grounds that more constraints make the underlying types more elegant and easier to read about. For the other side of the argument, read this Hacker News comment from a protobuf designer.

In my view, this debate comes down to how seriously you take the problem of changing schemas in a system with multiple consumers. If you want to add a required field to a protobuf, you have to do it like so:

- Add the required field to every service that creates the protobuf from-scratch

- Add the required field to any middlemen that are taking the protobuf and passing it on to some other system

- Add the required field to all other consumers

If you do this out-of-order, messages get dropped on the floor, likely causing some kind of production outage. Removing a required field requires a similar order-dependent process, except in reverse - consumers must drop the field first, followed by middlemen, followed by producers. If you forget to upgrade a consumer service schema (not as unlikely as it sounds, in large companies with thousands of half-forgotten services), the part of it that needs the protobuf will just stop working.

When you know all fields are optional, you can change protobuf schemas in a completely order-independent way. All services can upgrade to the new version of the schema more or less at their convenience. The tradeoff is that you won’t have the data until both you and the producer are upgraded to the new schema, so you’ll need to handle that case in your application code.

In case you couldn’t tell, I am very much on the Prococol Buffers side of the debate. Having done a lot of schema changes of various kinds, I think it is safer to tolerate incomplete data at the application level during a schema upgrade than be forced to upgrade services in the right order or risk an outage. In other words, I think application code should be willing to tolerate data that violates the domain model.

Final thoughts

The harder the constraint, the more dangerous it is. When I say that a constraint is hard, I mean that it is very difficult to undo it if you need to. A line of code validating something is a soft constraint, because you can simply remove the line if needed. Something baked into a database schema is a harder constraint, because it requires a migration to change, which (depending on the amount of data and the read volume) can be operationally very difficult. Some constraints are built into the architecture of the entire system: consider the “no data is ever truly deleted” constraint in blockchain or ledger-based systems.

For most software, domain models are not real. A domain model is only a model of real-world processes. Because of that, the constraints inherent to the domain model (like “tickets must always be marked as completed before being archived”) cannot be truly hard constraints. This is trivially true about most line-of-business or SaaS software, and gets less true the more generic and library-like your software is. If you’re writing a library to do efficient matrix multiplications, you can get away with much harder constraints than if you’re writing directly user-facing code. For much more on this, see my post Pure and impure software engineering.

I am not arguing that all constraints are bad. Constraints make a system possible to reason about, and the harder the constraint, the better it does its job. A system with no constraints at all (or only very soft constraints) is more of a programming language than a program. I like many kinds of hard constraint: for instance, I prefer protobufs to JSON, I like type signatures, and I strongly prefer relational databases with a set schema to schemaless databases. However, user-facing software will eventaully be forced to break many of its constraints in the interest of better fulfilling the real-world goal of that software. Thus, some invalid states ought to be representable.

edit: apologies to my email subscribers, the version of this that went out over email had a typo in the title (it read “representable” instead of “unrepresentable”).