Using AI chatbots actually reduces activity in the brain versus accomplishing the same tasks unaided, and may lead to poorer fact retention, according to a new preprint study out of MIT.

Seeking to understand how the use of LLM chatbots affects the brain, a team led by MIT Media Lab research scientist Dr. Nataliya Kosmyna hooked up a group of Boston-area college students to electroencephalogram (EEG) headsets and gave them 20 minutes to write a short essay. One group was directed to write without any outside assistance, a second group was allowed to use a search engine, and a third was instructed to write with the assistance of OpenAI's GPT-4o model. The process was repeated four times over several months.

While not yet peer reviewed, the pre-publication research results suggest a striking difference between the brain activity of the three groups and the corresponding creation of neural connectivity patterns.

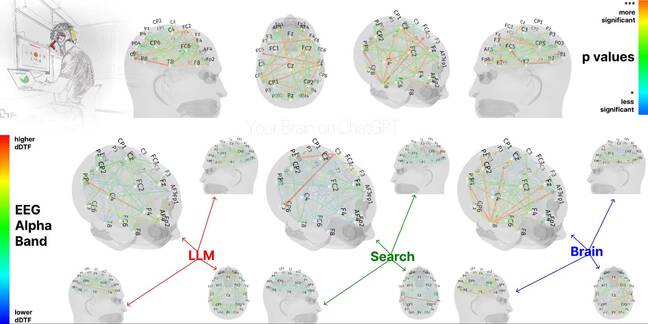

To put it bluntly and visually, brain activity in the LLM-using cohort was … a bit dim.

A look at brain activity in the three study cohorts (left to right: LLM, search and brain groups) the redder the colors, the more active the dDTF magnitude - Click to enlarge

EEG analysis showed that each group exhibited distinct neural connectivity patterns, with brain connectivity "systematically scaled down with the amount of external support." In other words, the search engine users showed less brain engagement, and the LLM cohort "elicited the weakest overall coupling."

Cognitive load in the participants was measured using a method known as Dynamic Directed Transfer Function (dDTF), which measures specific brain activity related to the flow of information across different brain regions. dDTF is able to account for the strength and direction of flow, making it a good representation of "executive function, semantic processing and attention regulation," according to the MIT researchers.

The researchers said that, compared to the baseline established by the group writing using nothing but their grey and white matter, the search engine group showed between 34 and 48 percent less dDTF connectivity. The LLM group, meanwhile, showed a more profound up to 55 percent reduction in dDTF signal magnitude.

Put simply, relying on LLMs - and, to a lesser extent, search engines - significantly reduces task-related brain connectivity, indicating lower cognitive engagement during the essay-writing task.

"The Brain-only group leveraged broad, distributed neural networks for internally generated content," the researchers said of their results. "The Search Engine group relied on hybrid strategies of visual information management and regulatory control; and the LLM group optimized for procedural integration of AI-generated suggestions."

As the researchers explained, those distinctions raise "significant implications" for educational practices and how we understand learning - namely in that there appears to be a definite tradeoff between internal synthesis of information and external support.

The LLM group's participants performed worse than their counterparts in the Brain-only group at all levels

Tests of participants on recall and perceived ownership of what they wrote were demonstrably worse in the LLM cohort, the research team found.

"In this study we demonstrate the pressing matter of a likely decrease in learning skills," the researchers said. "The LLM group's participants performed worse than their counterparts in the Brain-only group at all levels."

The fourth session of essay writing reinforced those findings. In the last research session, participants who were originally told to rely on their brains or LLMs swapped roles and were given another set of essay instructions. Unsurprisingly, the LLM group performed poorly when asked to rely on their own thought processes.

"In Session 4, removing AI support significantly impaired the participants from original LLM group," the researchers said. The opposite was true for the other cohort. "The so-called Brain-to-LLM group exhibited significant increase in brain connectivity across all EEG frequency bands when allowed to use an LLM on a familiar topic."

AI Chat: Generally Precludes Thinking?

The findings suggest that the use of AI early in the learning process "may result in shallow encoding" that leads to poor recall of facts and a lack of learning because all the effort has been offloaded. Using one's cognitive faculties to learn about something, and then using AI to further research skills, on the other hand, is perfectly acceptable.

"Taken together, these findings support an educational model that delays AI integration until learners have engaged in sufficient self-driven cognitive effort," the MIT team concluded. "Such an approach may promote both immediate tool efficacy and lasting cognitive autonomy."

That might not be a shocking conclusion, but given the increasing number of young people relying on AI to do their schoolwork, the issue needs to be addressed before the world produces an entire generation of intellectually stunted AI junkies.

Kosmyna told The Register in an email that she doesn't want to use words like "stupid, dumb or brainrot" to refer to AI's effect on us, arguing it does a disservice to the work her team has done. Still - it is having an effect that needs to be addressed.

"While these tools offer unprecedented opportunities for enhancing learning and information access, their potential impact on cognitive development, critical thinking, and intellectual independence demands a very careful consideration and continued research," the paper concluded.

With the paper yet to undergo peer review, Kosmyna noted that its conclusions "are to be treated with caution and as preliminary." Nonetheless, she wrote, the pre-review findings can still serve "as a preliminary guide to understanding the cognitive and practical impacts of AI on learning."

The team hopes that future studies will look at not only the use of LLMs in modalities beyond text, but also AI's impact on memory retention, creativity and written fluency.

As for what the MIT team plans to research next, Kosmyna told us the team is turning its attention to a similar study looking at vibe coding, or using AI to generate code from natural language prompts.

"We have already collected the data and are currently working on the analysis and draft," Kosmyna said. She added that, as this is one of the first such studies to be done studying AI's effect on the human brain, she expects this work will trigger additional studies in the future "with different protocols, populations, tasks, methodologies, that will add to the general understanding of the use of this technology in different aspects of our lives."

With AI creeping into seemingly every aspect of our lives at an ever-increasing pace, there's going to be plenty of research to be done. ®