A while ago, I have started working on authorization and authentication at work. This taught me a lot about how modern authentication systems work. However I have always thought One-Time Password logins are the most mystical ones. A six-digit code that changes every time and can be used to verify your identity. How does the server know the newly generated one, and how is it really secure? In this post, I will explain what HOTP, TOTP is and how they work by sharing my own implementation from scratch.

One-Time Passwords (OTPs) are a widely-used form of authentication. You’ve likely encountered them when using a “Secure Login” app like Google Authenticator, or during a “Forgot Password” flow where a temporary code is sent to your email or phone.

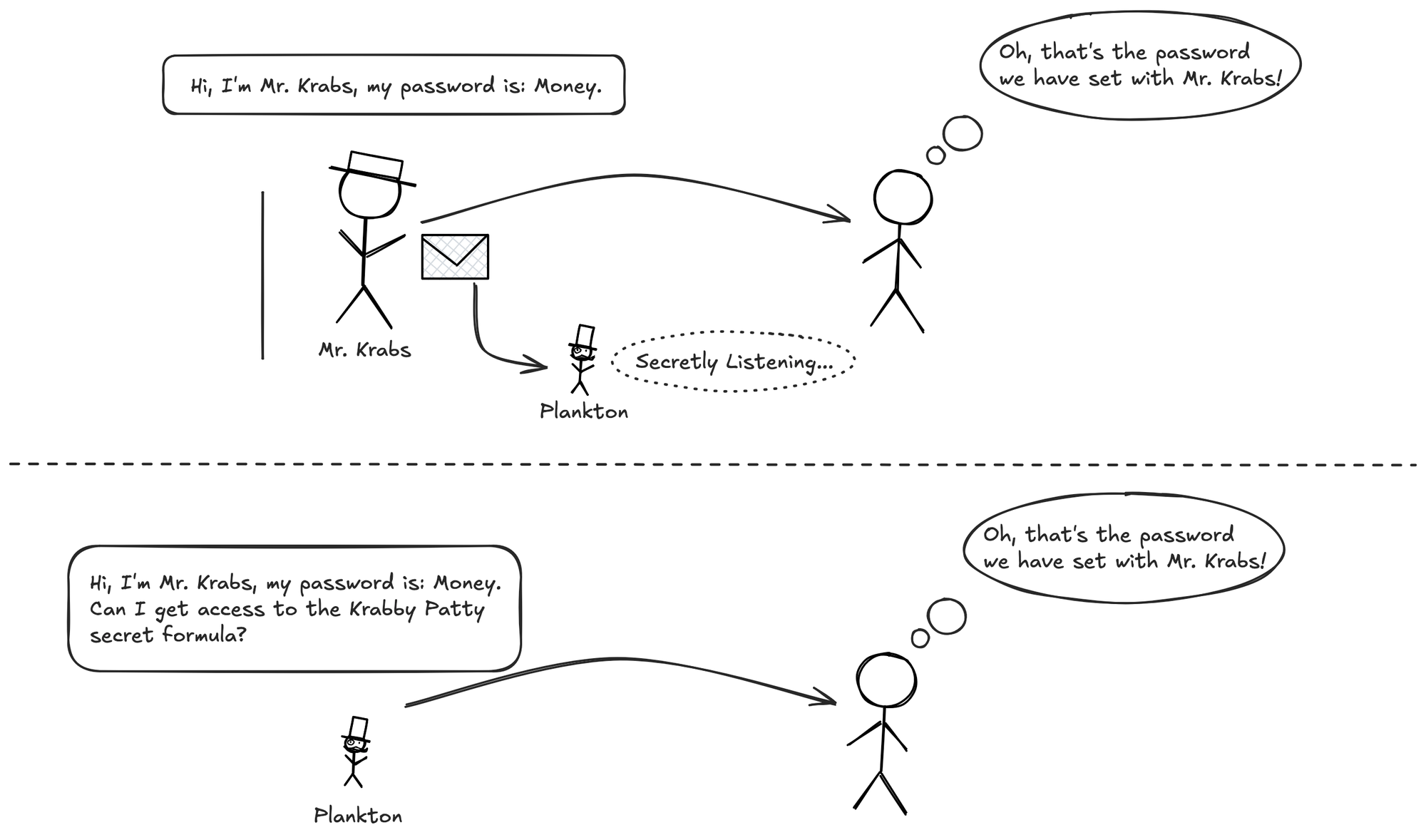

Unlike traditional passwords, OTPs are only valid for a single use or a limited time window. This greatly reduces the risk of password replay attacks, where someone captures the password used to login and tries to reuse it.

Like the traditional password authentication approach, the user and the authority (server) still needs to agree on a common secret key. During the regular password authentication, this secret key is directly communicated to the authority. There are many ways of doing this process safely, such as hashing the password or sending it over an encrypted network. However the risk still exists, as the password itself never changes, as long as we use our devices to type our passwords, there is some way those malicious actors can watch and get that information before it reaching the network.

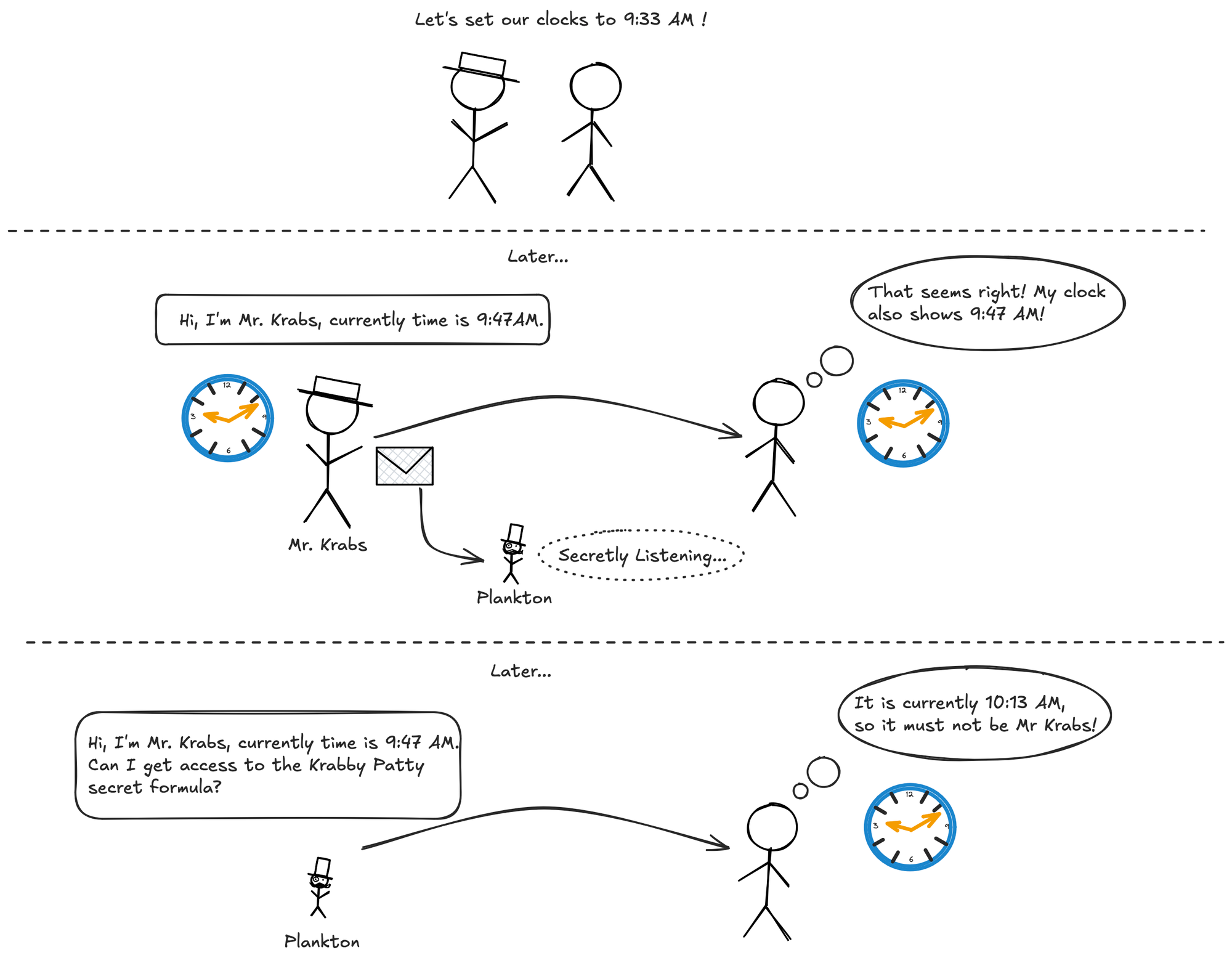

So instead of using a constant secret key, we can use something dynamic that changes over time. As a simple example, assume when those two people first met, they have set their secretly hidden clocks to a random time together.

Also in some examples like Facebook's password recovery, this secret clock is not shared with the user directly but rather server's generated one-time password is sent via a trusted medium, such as an email to the user.

Obviously a clock on its own is not secure, as in this example Plankton could have predicted the time-shift of the secret clock based on the real time. However for the sake of this example, I wanted to show how copying the "password" is not enough on its own. Let's take a look at some strategies to build this "secret clock" and make sure it is not possible to predict time just by knowing a single code in some point in time.

There are two common types of OTP algorithms:

- HOTP (HMAC-based One-Time Password) – based on a counter that increments every time an OTP is requested.

- TOTP (Time-based One-Time Password) – based on the current time, typically using 30-second intervals.

These methods are standardized in RFC 4226 (for HOTP) and RFC 6238 (for TOTP), and are used in many modern 2FA (two-factor authentication) implementations.

A counter based password method is easier to understand. Imagine two people met and generated a totally random series of numbers. They both start from count 0, as in each attempt, user needs to communicate to the server with the secret key in the given index. However this comes with several problems,

- Clients needs to sync their counter, if there is a skew, they might get temporarily locked out.

- Malicious actors can collect upcoming login codes by phishing the user and those codes can be used for a long time.

Therefore, instead of storing a counter, we can use the current time as the counter. That's how TOTP works. Using time makes synchronization easier, as many modern machines already use technologies such as NTP to sync their time and this prevents malicious actors from harvesting codes as their code will be valid for only next 30 seconds or so, not for a long sequence of future login attempts.

The analogy of two people met and decided on a totally random series of numbers is partially realistic. However it is not feasible to have such a huge list, you potentially need to have millions of secret numbers to support OTPs for a reasonable time. Therefore we should use algorithms that are cryptographically safe that generate values based on a secret key. It is important that this algorithm is not random, as both user and the authority will hold a copy of this secret key and they should be able to generate the same value given the same time.

We have introduced HOTP first because the actual implementation of TOTPs are actually HOTP based. Instead of using a static counter, TOTPs use the time as the current counter. We can write the following formula to find the counter in any given time,

\[ c(t) = \left\lfloor \frac{t - t_0}{X} \right\rfloor \]

Here \(t_0\) is the starting time, in most systems this is the default UNIX epoch timestamp, 1 January 1970. \(X\) is the period you want the code to rotate. For example, if you want the login code to change every 30 seconds, X should be 30 seconds.

In order to generate an HOTP, you need to decide on three things:

- A secret key

- A hash function

- Number of digits you will output

First, we need to start by hashing our secret key. For example, if we have chosen SHA-1 as our hashing algorithm, our output would be only 64 bytes. If secret key is shorted than 64 bytes, we can just pad it with zeroes. Otherwise, given \(K\) is our secret key and \(H\) is our hashing algorithm,

\[ K_{pad} = H(K) \]

Later we do an XOR operation on text with some pre-defined magic constants \(I_{pad}\) and \(O_{pad}\).

\[ I_{pad} = [\texttt{0x36}, \dots] \newline O_{pad} = [\texttt{0x5c}, \dots] \]

Those numbers are originally chosen by HMAC designers and any pair where \(I_{pad} \neq O_{pad}\) could have been chosen. Their lenght should be also 64 bytes, same as our hashing algorithm's digest length. Later we define the famous \( \text{HMAC} \), Hash-based Message Authentication Code, function. It outputs a crypthographic hash calculated using the given key and message.

\[ \text{HMAC}(K, M) = H(K_{pad} \oplus O_{pad} + H(K_{pad} \oplus I_{pad} + M)) \]

This cryptographic hash function is secure, so that user can't infer the secret key \( K_{pad} \) even if they knew \( M \) and the resulting hash.

Later we will define a new function to generate a 4-byte result. Here is the definition of DT from the original RFC,

DT(String) // String = String[0]...String[19]

Let OffsetBits be the low-order 4 bits of String[19]

Offset = StToNum(OffsetBits) // 0 <= OffSet <= 15

Let P = String[OffSet]...String[OffSet+3]

Return the Last 31 bits of PThis function allows us to shrink our 20 byte input to 4 bytes dynamically by choosing the bytes offsetted by the number that is represented using the last 4 bits of the input. The outputs of the DT on distinct counter inputs are uniformly and independently distributed.

Finally, we can define our HOTP function as,

\[ \text{HOTP}(K,C) = \text{DT}(\text{HMAC}(K,C)) \bmod 10^{\text{digits}} \]

Here we can replace our counter \( C \) with \( c(t) \) to get a TOTP code.

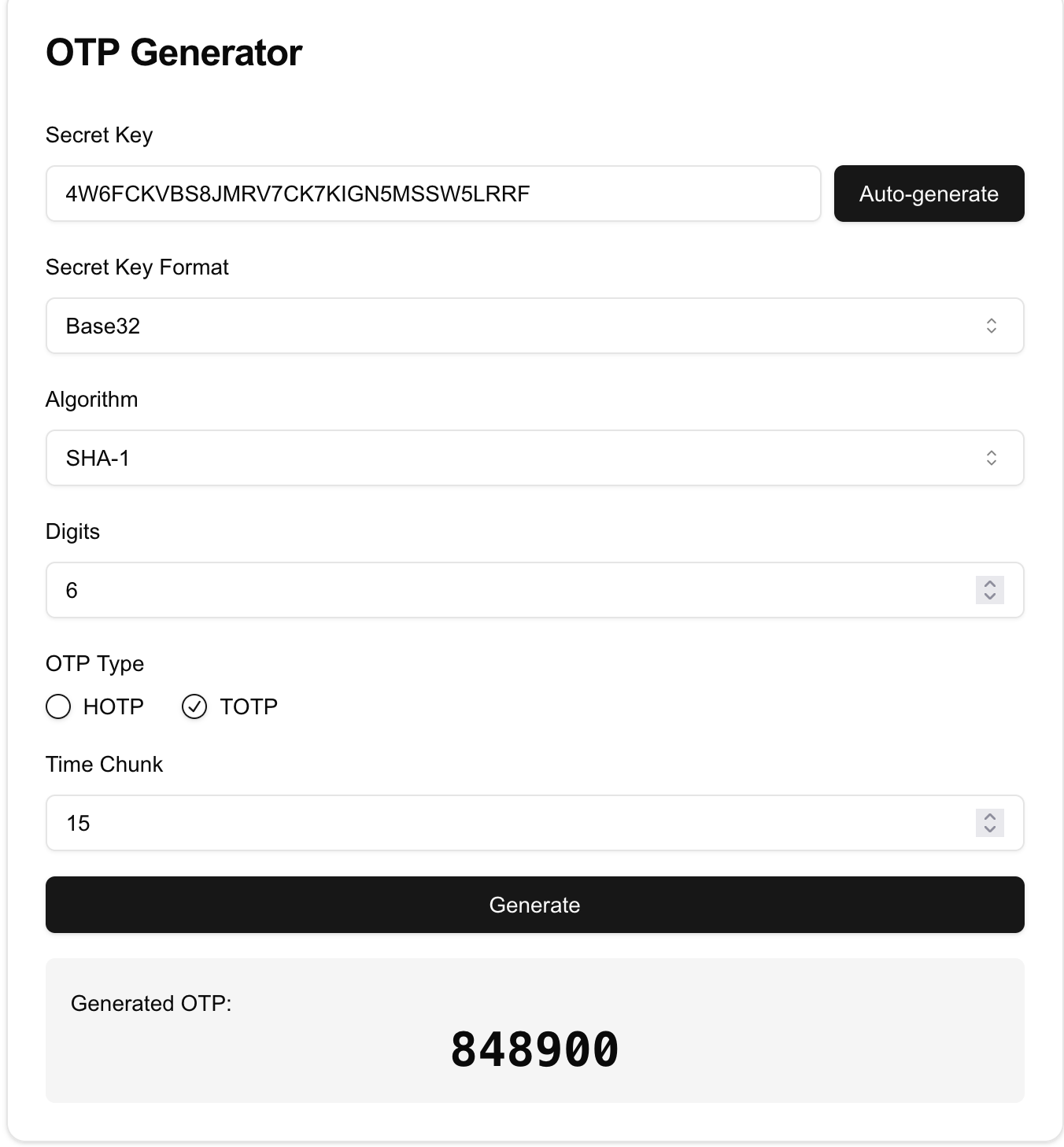

There are many online resources with TOTP and HOTPs, however I have struggled to find a website that help me check my implementation as their secret-key representations were not standardized. Thus, I have published my own short demo app to showcase.

OTP Generator

Test and validate OTP workflows such as TOTP and HOTP.

I have published this app on my website and also on GitHub, the implementation uses Kotlin.

To recap: We’ve looked at how HOTP and TOTP work, explored how they're derived from HMAC, and saw how the server and client can generate matching codes without ever transmitting the password itself.

Working on this project helped me understand how OTPs work at a much deeper level. What once felt like magic now feels like elegant design.